by Gregory Seay

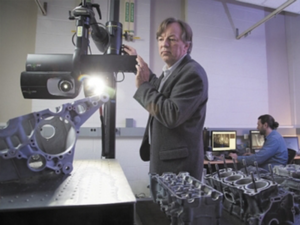

East Hartford’s Bolton Works relies on technology for generating three-dimensional images that has allowed manufacturers to churn out countless parts made to minutely precise tolerances or specifications.

Called metrology, Bolton Works uses 3-D scanners to carry out precision checks on jet-engine parts for East Hartford’s Pratt & Whitney, and on manufactured components from other commercial-industrial customers.

“Anything that’s manufactured needs to be inspected at some point,” said Mark Bliek, founder and president of the three-person shop housed in a small corner of the Connecticut Center for Advanced Technology on Pratt & Whitney’s campus. “You need to know it meets your design intent.”

But 3-D scanning, as Bliek has long known and a cadre of UConn engineering pupils have learned, also can be invaluable for reverse-engineering parts and components — while generating new revenue-producing business opportunities.

Since 2014, UConn students have tapped Bolton Works’ 3-D scanning expertise to produce a more powerful motorcycle engine to propel their lightweight, open-wheel race car into an annual international competition that challenges college pupils to design, develop and race a Formula-style race car.

The latest Society of Automotive Engineers annual Formula SAE competition, as the race is known, will feature some 119 college teams — including UConn — May 10-14, at Michigan International Speedway.

In addition to helping local students, Bliek says his shop’s work for UConn in the Formula SAE challenge has exposed Bolton Works’ technology and talent to a wider audience — in Connecticut and across the U.S. and the world.

Indeed, demand and backlog for Bliek’s services, he said, have prompted him to search for larger quarters, around 3,000 to 4,000 square feet, for his company.

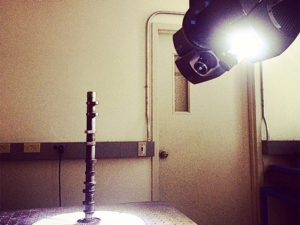

According to Bliek, 3-D scanning for metrology or reverse engineering requires vast sums of digital data generated by bathing a component in beams of light that can be picked up by the scanner’s optics.

The digitized data is then processed via computer, to display onscreen 3-D images of the part. When the part is a single unit, like an impeller blade for a turbocharger, the scanning chores are relatively easy.

But the dozens of parts making up an older 105-horsepower Suzuki GSX-600R engine, and another newer 600 cc, 105-horsepower engine from Yamaha — which UConn wanted to reverse engineer — presented Bolton Works with a real challenge for precision and timeliness, Bliek said.

The reverse engineering was necessary because Suzuki, along with Honda, Kawasaki, Yamaha and other motorbike- and automobile-engine builders, loathe sharing with outsiders the proprietary technology embedded in their products, he said.

This year, Team UConn opted to switch to a more modern Yamaha engine, officials say, with more readily available parts that competition rules allow teams to modify for greater horsepower.

But the team also needed the Yamaha engine to fit precisely into the space frame and chassis already assembled. For that, they needed a “blueprint” of the engine and its components, one that Bolton Works provided the UConn team using its 3-D scanning expertise.

It took one day just to scan the assembled engine and build the 3-D data file, Bliek said. Then, the engine was disassembled, and images taken of the engine block, pistons, crankshaft, valves and other components — 25 in all — work that took seven more workdays.

Using all the digital data, Bolton Works took nine more days to generate a virtual, computer-aided design (CAD) replica of the engine, with all its components, Bliek said. In all, it took about a month to reverse engineer the Yamaha motor, he said.

Word of Bolton Works’ efforts for UConn’s race team spread fast among the close-knit Formula SAE community. Since then, the firm has done the same reverse engineering and modeling of the Honda four-cylinder CBR600RR and Yamaha YZF-R6 engines. Those engines are used by more than 20 Formula SAE teams worldwide, UConn said.

“His process allowed us to bring in a true 3-D model of a new engine into the same drawing program we designed the frame in,” said Tom Mealy, UConn’s adjunct professor of mechanical engineering and faculty adviser to the school’s Formula SAE race team.

Bolton Works did its UConn work gratis, but charged the other college teams a nominal fee that Bliek declined to reveal. He also wouldn’t share any financials for his closely held firm, except to say it’s profitable.

Bliek says he’s also involved in a side project in which his equipment is scanning hard-to-replace parts from a WWII Navy Corsair fighter plane that a Chester man is refurbishing.

Bliek, originally from The Netherlands, launched his company in 2004 in his Bolton home, thus its name. His business model, he said, relies on metrology tools certified by the U.S. Commerce Department’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to verify the accuracy of his 3-D scans for customers.

“That’s very important to them,” he said of his customers. “In the beginning, we didn’t know what we were doing, because we couldn’t verify the accuracy.”

After more than a decade of mostly trial and error, Bliek has settled into a routine that allows him and his crew to get their work done as quickly and efficiently as possible.

With a $50,000 Small Business Express Program loan through the state Department of Economic and Community Development (DECD), Bolton Works purchased a $25,000 Fanuc robot arm. The arm tirelessly “grips” all sorts of parts, holding them in an infinite number of angles and positions, so the scanner can collect a full 3-D picture.

But just when Bliek thought things were looking up, he arrived at work one day to find the state DECD had opened a demo 3-D scanning center right next door in the CCAT facility.

Bliek was already searching for larger quarters, to house perhaps two more 3-D scanning technicians.

“It’s also a good time for me to move along,” he said.